Unbelievable part 29: The Minotaur

TW: sexual violence, rape

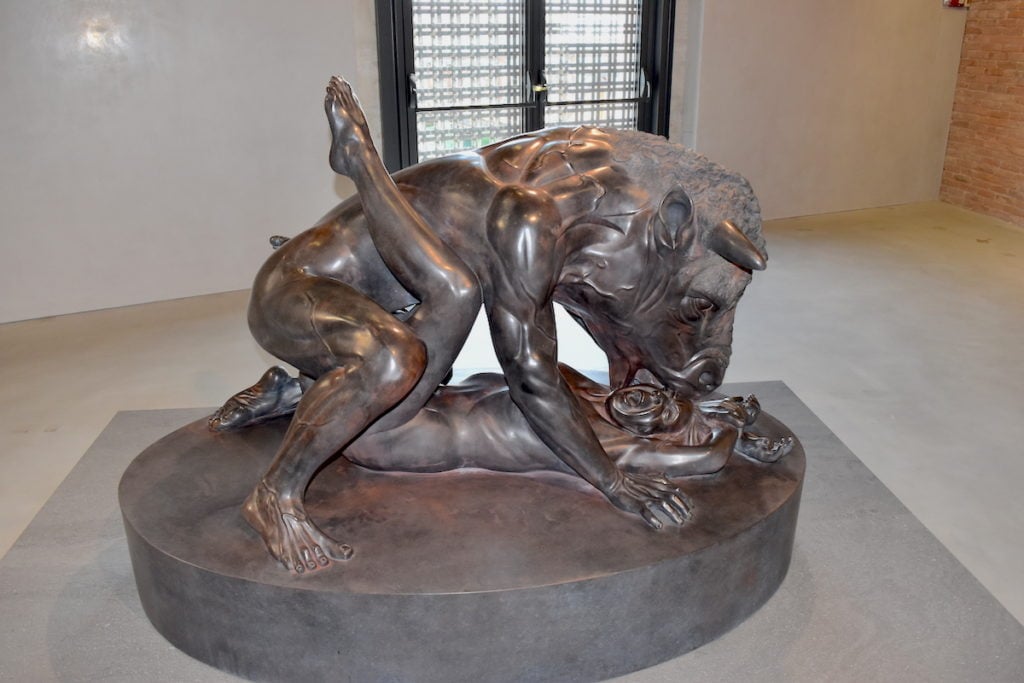

The Minotaur (Damien Hirst, 2012, image from art.net)

This depiction of the half-man, half-bull of Greek myth raping an Athenian virgin presents the violent threat of unfettered male sexuality. Greek and Roman myths abound with brutal stories of the sexual assault of women by men and gods alike. Classical art often aestheticized such scenes, sanitising any explicit reference to intercourse. In myth, such assaults were partly rationalised by claiming that the god Eros was capable of overpowering male bodies and wills at any moment. This pre-Freudian distinction between the conscious and unconscious suggests the Minotaur – which has remained a symbol of sexual violence and male lust, most prominently in the work of Picasso – might here be read as a horrific embodiment of the sleep of reason.

(Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable guide p. 33)

The sleep of reason. From whose perspective? In my experience rapists take what they feel they deserve. What’s owed to them. What should be provided for them because it is their entitlement. It is their self-perceived power that allows it. Demands it. The Minotaur of Crete whose name was Asterion (meaning star) was an unfortunate creature, borne of deception and vengeance. His mother, Pasiphae, was the wife of King Minos of Crete, and his father was a white bull gifted to Minos by the god Poseidon. Rather than sacrifice the bull as instructed, Minos thought it too magnificent to kill and substituted it, taking Poseidon for a fool. The Olympian did not respond kindly to this and made Pasiphae develop an insatiable lust for the bull to humiliate Minos. Pasiphae had the architect and craftsman Daedalus construct a hollow wooden cow for her to adorn to attract the bull. Asterion was the result of this bestial union.

Pasiphae tried to love her monstrous son, but as an unnatural creature his appetites could not be satisfied and he became too large and dangerous to keep in the palace at Knossos. Daedalus and his son Icarus were commissioned to create a labyrinth to hold Asterion. Converging with this story, an older son of Pasiphae and Minos was killed in Athens, in reparation for which Minos demanded fourteen youths – seven female and seven male – to be sent from Athens as a sacrifice. Upon delivery, they were trapped in the labyrinth and the horrors they encountered are left up to the most troubled parts of our imaginations.

The sexual violence depicted so graphically in Damien Hirst’s The Minotaur visualises one such aspect of this imagined horror. Most characters’ sexualities and appetites in general are super-charged in the Greek myths, so why not Asterion’s, especially given his own debauched creation? As the exhibition guide text points out, such imagined realities have historically been aestheticised and sanitised throughout art history. Does this mode of silencing merit such a confronting and anatomically detailed depiction? This is so often a paradox central to Hirst’s work: to show is exploitative, but to not show would be diminishing just like all the rest. His response is to go all-in and give viewers permission to feel offended, or indeed, titillated. Perhaps at our most honest we feel both concurrently.

The strangest part of seeing the whole of Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable – which I cannot stress enough was a thoroughly weird experience in all – was when Jenn and I reached The Minotaur and were struggling to decide how we felt about the ambivalence around showing a life-size rape so vividly, another woman started intensively photographing the sculpture. It was as if we were witnessing a pornographic photo shoot. She was kneeling down and getting the camera right up to the anatomically correct bits and pieces. The gluteal muscles mid-thrust. The young woman’s screaming face. Her writhing body pinned down by the huge man-beast. His gripping feet. Their webs of taught muscles. His left hand pressing her bound wrists above her head. The ambiguity over her expression of pain or pleasure with her left leg almost hooked up around his torso, her foot pointing upward, and not pushing against his thigh in an attempt to kick him off....

Do you see how easy it is to slip into victim-blaming just from projecting onto a surface image? When you’re scrutinising her body to detect the merest signs of sexual pleasure from her attack? To write off his actions as being in his nature? The way his mouth straddles the right side of her head makes him look as if he could be about to bite her face off or panting against her cheek in the throes of passion. No matter what it looks like from the outside, he is consuming this anonymous Athenian (representing so many – too many – of us) against her will.

The sculpture is what it is, but what to make of the photographer? Or the detail she seemed to be capturing? What of the performance of her snapping like a paparazza, like Thomas (David Hemmings) in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up and as parodied by Mike Myers in Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery? Frenzied photography. Consumptive rendering. Of female models being straddled by male photographers while the camera’s merciless and impersonal gaze penetrates them. In the gallery space, we didn’t know what to make of a woman photographer who looked as if she was practically, but not quite, doing the same with this granite sculpture. Do her actions indicate anything about our desire to not just see but to interrogatively witness the quotidianly unthinkable? Is it a demand to see truth? Is it a fetish? Is there a difference?

I often wonder about the production process with these kinds of works when they must have involved living models to make the initial casts. While you might assume that granite could only be carved, as with marble, there are now processes by which hard igneous rocks can be ground into a powder and mixed with resin to make it pourable and settable within a mould then finished by hand. Still, this black granite sculpture in the flesh and in photographs looks indistinguishable from new dark bronze as seen through much of the rest of the show. It has certainly been buffed to a sheen, giving an almost greased look to the Minotaur's bulging muscles and inviting light to accentuate the contours of the young woman’s body, even down to her protruding ribs and bared teeth. Is there a glamourising of the situation? Or is it normalising? Is one worse than the other?

The exhibition confronted its visitors with a number of realistic elements typically absent in, well, art in general. A number of sculptures included visible labia. There were intersexed statues. There were damaged, injured and disabled bodies. There was body horror of many kinds. There was death. There was a wide range of violence including infanticide, animal attacks, shootings, maiming, and impending one-on-one battles. Rape as an exertion of control coming from one who has no control over his life is utterly tragic. Tragic still is that he will die at the hands of a celebrated hero, Theseus, who will make promises he has no intention of keeping to Asterion’s sister Ariadne to ensure her help only to abandon her on Naxos on the way back to Athens. During this same voyage Theseus will neglect to change the ship’s sail to alert his father, Aegeus, that he is alive, leading the grief-stricken King of Athens to throw himself off a cliff, and so leaving the throne to Theseus. With heroes like these, who needs enemies? Asterion’s victims were also Minos’s victims. Is there a worse option: a victim-perpetrator or a disarmingly charming perpetrator? I’m not sure I’ll ever have answers to all of these questions.

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe and visit buymeacoffee.com/peablair to support my work - thank you!

Comments

Post a Comment