Exemplary Essay for Introduction to Scholarly Practice

My partner runs a module that introduces scholarly concepts a practices to new undergraduate students, and to give them the best possible start to their university careers, he provides exemplary essays as examples of high quality first-year work. This is one he commissioned me to write back in autumn (paid me and everything) as it's about social media, which he does not do, and I do too much. This is a substantial rewrite of an essay by a student , the topic chosen by them, but it wasn't up to his high standards. There was maybe 2-5% of the student's work left by the time I re-researched and re-wrote it. About the Charlie Hebdo hashtags, I thought it might be interesting to share. Content is content is content.

5. Using any social media site of your choosing, select any post-2000 cultural event and demonstrate one trend amongst its audience.

Discuss the dual Twitter hashtags #JeSuisCharlie and #JeNeSuisPasCharlie as an example of post-event debate.

In September and October 2020, a familiar pair of hashtags that had previously signalled a significant debacle around freedom of speech more than five years earlier began trending again on Twitter. Since January 2015, #JeSuisCharlie (#IamCharlie) and #JeNeSuisPasCharlie (#IamNotCharlie) have indicated allegiance to sides of ever-erupting furores over the provocative covers published by the French satirical weekly cartoon magazine Charlie Hebdo. With reference to Fabio Giglietto and Yenn Lee’s sociological study of the discursive strategies they identify around these hashtags that emerged following the Charlie Hebdo massacre in 2015, I detail the tendencies in Twitter users to split off into polarised factions, as denoted by the use of hashtags as ‘shared conversation markers’ (Bruns, 2011: 1323). In showing how the negative hashtag in particular continues to be a phenomenon in 2021, and by looking at this in light of the ways that Twitter’s algorithms work to maintain users’ attention, I aim to show how the micro-blogging site provides a platform for debate and protest while facilitating its own commercial interests by determining ways that users will engage with and react to such debates.

As seen in the Arab Spring uprisings and unrest in the early 2010s, social networking sites such as Twitter have gained traction as spaces and tools for starting or complementing real-world protests and social, political and cultural movements. Given that Twitter aims to keep users on the site, the success of hashtag campaigns is inextricably linked with the ability of the site’s algorithms to influence users’ behaviours and opinions. Twitter’s trends are determined by the frequency of hashtags, words and phrases that appear and are liked (previously favourited) and retweeted on the platform in a given hour combined with individual users’ locations and interests based on what trend terms they click on, tweets they spend time with and accounts they follow. Given these methods that curate a timeline or newsfeed (now called ‘Home’, the welcoming connotations of which no doubt add to the pull of endless scrolling), it is easy for users to become engrossed in current affairs topics and to pour over (an act known as ‘doomscrolling’) the glut of comments (colloquially referred to as ‘hot takes’) on events as they unfold. It is equally as easy for users to be drawn into the fray and show their advocacy for one side or another, as was the case following the Charlie Hebdo massacre.

On 7 January 2015, Algerian French brothers Chérif and Saïd Kouachi forced their way into the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris armed with assault rifles. They killed a dozen people and injured a further eleven. They identified as members of the Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda, specifically, the Yemen branch called al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula which claimed this and related attacks days later, including the murder of a police officer and shootings at a Jewish market. The shooters asserted that they were enacting revenge for the magazine’s derogatory portrayals of the prophet Muhammad. After the shootings, the public gathered to hold unity demonstrations with many chanting ‘Je Suis Charlie’. When the Charlie Hebdo website came back online after being shut off due to the attack, the homepage displayed a black background with this phrase in the bold white block-capital lettering of the magazine’s title font. The hashtag #JeSuisCharlie quickly emerged on Twitter, reflecting international outpourings of solidarity, empathy and condolence. Along with the message of unity, the slogan expressed support for the magazine’s right to free speech and its editorial independence regarding any topic, including religion (Giglietto and Lee, 2017: 1). The hashtag was repeated around seven million times in the week following the shootings, and at the time was reportedly one of the most repeated news-related hashtags in Twitter’s history (Wendling, 2015). Twitter had become host to a freedom of speech movement with millions of accounts expressing their support and determination to defend free speech through changing their profile pictures to a black background with the hashtag in white, as well as circulating the magazine’s previously published cartoons along with new ones specifically referencing the movement.

Shortly after #JeSuisCharlie emerged, #JeNeSuisPasCharlie appeared in opposition, explicitly challenging the identification and solidarity with the inflammatory magazine. The users of this hashtag countered what they saw as unconditional support for Charlie Hebdo, and many accused the magazine of hate speech and discrimination. As Giglietto and Lee point out, since the initial hashtag ‘was about a tragedy of 12 deaths and the fundamental right to freedom of expression, #JeNeSuisPasCharlie carried an inherent risk of being viewed as disrespecting victims or endorsing the violence committed’. This counter hashtag was nevertheless shared more than 74,000 times in the days following the attack (Giglietto and Lee, 2017: 1). More specifically, Giglietto and Lee’s ‘dataset consisted of 74,074 tweets containing the hashtag #JeNeSuisPasCharlie published by 41,687 unique users between 7 and 11 January 2015’ (2017: 4), meaning that a significant amount of the tweets were in fact retweets rapidly sharing what other accounts had said.

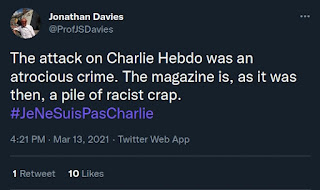

As well as expressing sides of a debate, in leading with ‘I’ and personalising the message, #JeSuisCharlie and #JeNeSuisPasCharlie also communicate political opinion linked with a sense of identity. Other examples of hashtags in this category include #BlackLivesMatter (signalling oneself as an anti-racist) and #MeToo (signalling oneself as a victim of sexual assault or harassment), which have also gained significant momentum throughout the 2010s and into the 2020s. Regarding #JeNeSuisPasCharlie, Giglietto and Lee identify three phases correlating with three peaks in the hashtag’s usage on 7, 8 and 9 January 2015. In the first peak beginning just over an hour after the first appearance of the fast-trending #JeSuisCharlie, the counter tweets expressed condolences and grief for the shooting victims prior to stating a negative opinion of the magazine (2017: 7). Such caveats were rarely offered as the hashtags trended again more recently in September and October 2020 and March 2021 following the magazine’s re-publication of Muhammad cartoons and depictions of Meghan Markle and the dead 3-year-old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi which many users found offensive. The screenshot below of a tweet by @ProfJSDavies dated 13 March 2021 is as sympathetic as my searches have found on the recent usage of the hashtag, stating: ‘The attack on Charlie Hebdo was an atrocious crime. The magazine is, as it was then, a pile of racist crap. #JeNeSuisPasCharlie’.

|

| Screenshot of a recent example of the ‘I am not Charlie’ hashtag’ |

The above tweet is indicative of the general mood evoked by posts tagged with #JeNeSuisPasCharlie, both in 2015 and more recently. As Giglietto and Lee’s data-scraping research found, the tone became increasingly vitriolic in those days following the attack. They state: ‘[i]n the second phase, “Resistance,” the users started to voice out their reservations more loudly. In the last phase, “Alternatives,” the users offered alternative frames for Charlie Hebdo cartoons, such as hate speech, Eurocentrism, and Islamophobia’ (2017: 7). Across these initial three days, the negative hashtag evolved from simply pointing out that Charlie Hebdo should not be synonymous with free speech to using its own material to express that it is part of the problem of engendering an unwelcoming and unsafe environment for ethnic and religious minorities in Europe.

|

Examples of tweets using Charlie Hebdo’s own images as indicative of its racism. |

The above screenshots show the continuation of such alternatives to the magazine’s provocations where instead of speaking out for the magazine’s right to free speech that calls out hypocrisy regardless of who takes offence, the images are themselves taken to be hypocritical and racist. To the left, on 30 August 2021 @AnarchisteLol used the hashtag while quote-tweeting @Charlie_Hebdo_ to declare ‘Abjection’, making clear their distaste at the magazine’s quiz entitled ‘Are you ready to welcome an Afghan?’ following the fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban. Rather than take this question as an invitation to confront their own ‘clicktivism’, or performative online advocacy, such users see this as part of an accumulating narrative of the publication’s Islamophobia. The screenshot above right shows a quote-tweet by @BlackJackDrixx of a thread by @Nadine_Writes that begins with the magazine’s 10 March 2021 front cover and states of it that it ‘mocks George Floyd's murder and Meghan's racism concerns. The cover reads: “Why Meghan left Buckingham Palace”, “Because I couldn't breathe”.’ Just as the dual ‘I am/I am not Charlie’ hashtags are often attached to highly polarised posts, the responses to this thread either strongly agree that picturing Meghan Markle being choked by Queen Elizabeth II in the vein of police officer Derek Chauvin’s murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020 is as insulting to black people as depictions of the prophet Muhammad are to Muslims. However, many accounts, mainly originating from France and the United Kingdom, posit that although it lacks tact, the image represents the more privileged end of a black or mixed-race person’s experience of white supremacy that is nonetheless part of an oppressive system. I would add that it does not seem to occur to the users of #JeNeSuisPasCharlie who also screenshot and quote-tweet Charlie Hebdo that they are adding to the circulation and reach of what they view as harmful images, and are thus adding to analytics that inform Twitter about what is popular and attracts high engagement and will be circulated all the more on the platform.

In chronicling the complex history of freedom of expression to ponder its status in the digital age, with reference to broadcast media largely in the United States, Richard R. John states that:

[f]ree expression norms have historically presumed that the network providers are legally responsible for their content and that their audience is spatially bounded and temporally limited. Neither of these conditions can be taken for granted on the web. Protected from prosecution by section 230 of the 1996 U. S. Communications Decency Act, Facebook and Google lack a compelling rationale to monitor their content. (John, 2019: 34)

We can assume this equally applies to Twitter, which is highly likely given how much active harm one needs to openly commit to be banned by the platform, as shown in the case of Donald Trump following the insurrection on the Capitol Building, Washington, D.C., in January 2021. John continues that while in the past pluralism within which individuals could be held accountable was encouraged, we are now dealing with:

multibillion-dollar digital media platform providers [...] that are legally absolved from any liability for the information that they circulate, deny that they are in fact media outlets by claiming merely to be neutral, algorithm-driven platforms, and have arrogated to themselves the authority to alter at will the media streams of millions of people. (John, 2019: 34)

A major issue here is that most users of Twitter are not privy to this information, and their thoughts which would previously have been kept to private spheres are thereby unwittingly exposed to global audiences and more vulnerable to the widespread veneration of strangers than at any point in human history before the 2000s.

#JeSuisCharlie and #JeNeSuisPasCharlie persist in acting as cyphers for debates around freedom of expression and often accompany examples of divisive publicly stated opinions. Importantly, they serve as urgent reminders of the need for clarity in free-speech laws, and are indicative of the struggles law-making faces in catching up to the rapid developments facilitated by largely untempered post-2000 social media communications. Where Twitter is concerned, it is served by allowing its users to believe they are engaging in activism when using the site to broadcast an opinion with a related hashtag when, in fact, its existence and revenue rely on user-generated content – content that leads to real-world effects, and not always in the modes of social change many users imagine themselves engendering from their keyboards or phones. What is alive and well is the right to be offended on a public stage and to offer unfettered retaliations with no consequence to the platform. The aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre is still playing out on Twitter via users showing increasing anger and frustration with the magazine or towards other users for their alternative readings of the magazine’s content. Beyond the tragedy that led to this ongoing debate, #JeNeSuisPasCharlie provides an example of the ways Twitter’s algorithm facilitates public arguments between strangers to ensure its own success.

Works Cited

Bruns, A. (2012) ‘How Long Is A Tweet? Mapping Dynamic Conversation Networks On Twitter Using GAWK and GEPHI’, Information, Communication & Society, 15(9), pp. 1323-1351.

Donohue, B. (2015) ‘Muslims are right to be angry’, Catholic League, 7 January. Available at: https://www.catholicleague.org/muslims-right-angry/ (Accessed: 6 January 2021)

Giglietto, F. and Lee, Y. (2017) ‘A Hashtag Worth a Thousand Words: Discursive Strategies Around #JeNeSuisPasCharlie After the 2015 Charlie Hebdo Shooting’, Social media + society, 3(1), pp. 1-15.

John, R. (2019) ‘Freedom of expression in digital age: a historian’s perspective’, Church, communication and culture, 4(1), pp. 25-38.

Wendling, M. (2015). ‘#JeSuisCharlie creator: Phrase cannot be a trademark.’ BBC News. 14 January. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-30797059 (Accessed: 5 January 2021)

Comments

Post a Comment